Quantum Computing For Complete Noobs

Learning the Basics of Shor's Algorithm After Reading a Grifter Pop Sci Book

I was browsing the bookstore a few months ago and came across Quantum Supremacy by Michio Kaku. After reading through the book recently, I found Scott Aaronson’s takedown of the book and found that Kaku seems to be generally regarded as a grifter and hypeman by the actual physics community.

The common retort to critiques of popular science is that books like Quantum Supremacy are made for laypeople, and they must perform some abstractions to make their topics digestible that will naturally make experts like Aaronson cringe. As a layperson myself, I do agree that any small factual errors Kaku makes are most likely forgivable. What I instead find most irksome about this brand of popular science is how performative and substance-less the book is. Kaku seems more interested in name-dropping Albert Einstein, the Nobel Prize, and mathematical Greek letters and buzzwords than actually explaining the key gap in understanding that most laypeople have of quantum computing: how do we make the leap from something as useless and abstract as quantum physics into something concrete and powerful enough to break all of modern encryption?

To develop some intuition about this question, it is probably easiest to directly look at an overview of Shor’s Algorithm for using a quantum computer to factor a large product of two primes and therefore break all of modern encryption. This overview is based off of this YouTube video and chatting with ChatGPT. Apologies to any quantum physics non-noobs for any factual errors.

At the heart of quantum physics is the idea that a system can exist in multiple states simultaneously, a concept known as superposition, until it is measured. This is famously illustrated by Schrödinger's cat, a thought experiment in which a cat in a sealed box is linked to a quantum event (like radioactive decay). Until the box is opened and observed, the cat is considered to be in a superposition of both "alive" and "dead."

This measurement problem can be empirically seen in the double-slit experiment (this website has great resources on the double-slit experiment and quantum physics for dummys). If you fire electrons one a a time through a sheet with two slits onto a wall, the pattern they make on the wall will be as if each electron somehow passed through both slits at once. However, if you try to measure which slit each electron goes through, somehow the electron “knows” it is being measured and will only pass through one slit, and the pattern on the wall will reflect as such. The reason that quantum physics seems so theoretical and abstract is that it’s impossible to observe; once you try to observe some particle existing in multiple states, it immediately collapses to a single state.

The idea behind quantum computing is to leverage the fact from quantum physics that the world can exist in many states at once in order to perform parallel computation to solve real-world problems. However, in the real world, the moment that we measure a quantum particle, it randomly collapses to a single state according to a distribution. Thus, the key challenge in quantum computing is how can we manipulate this distribution to amplify the probabilities of certain states to make a quantum computer reliably collapse to a useful state.

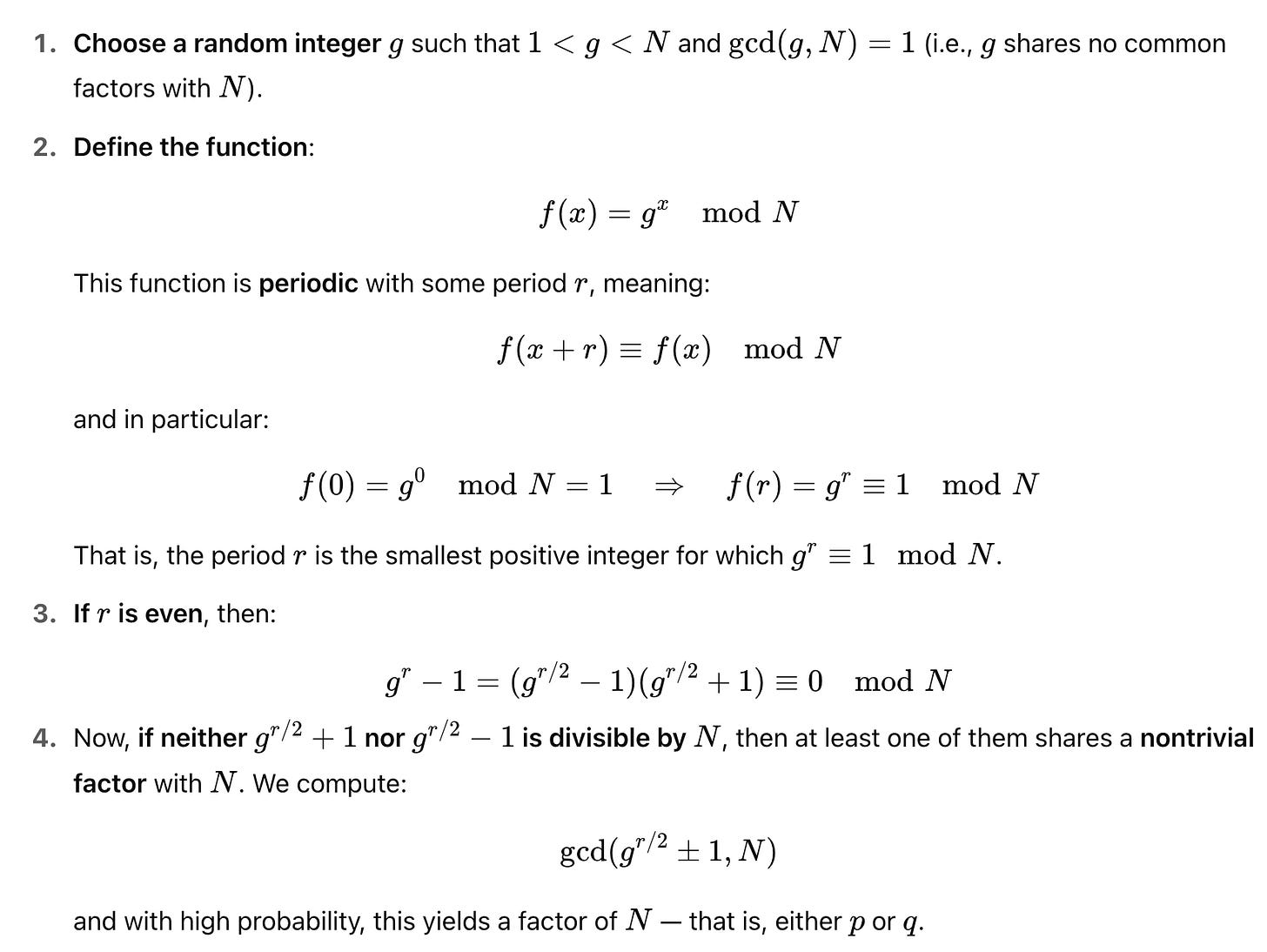

Here is how Shor’s algorithm gets around this problem. Suppose we are trying to factorize a product of two large primes N=pq (and thereby crack RSA). We can do the following:

We can use the quantum computer to find r, after which it becomes straightforward to factor N provided r is even (if r is odd, you simply try again with a different g), by doing the following.

The fundamental building block in a quantum computer is a qubit. Each bit exists in a state of super-position, meaning that it is simultaneously both 0 and 1. If you have a n-qubit representation, you simultaneously represent 2^n states, which is extremely powerful. However, once you try to measure the representation, you will merely randomly get one of the possible 2^n states.

We start with a representation of n qubits, which simultaneously represents all integers 0 through 2^n-1, and transform our representation into f(x) = g^x mod N for all integers x. However, we cannot yet measure our representation now, because that will simply randomly give us f(x) for a random integer.

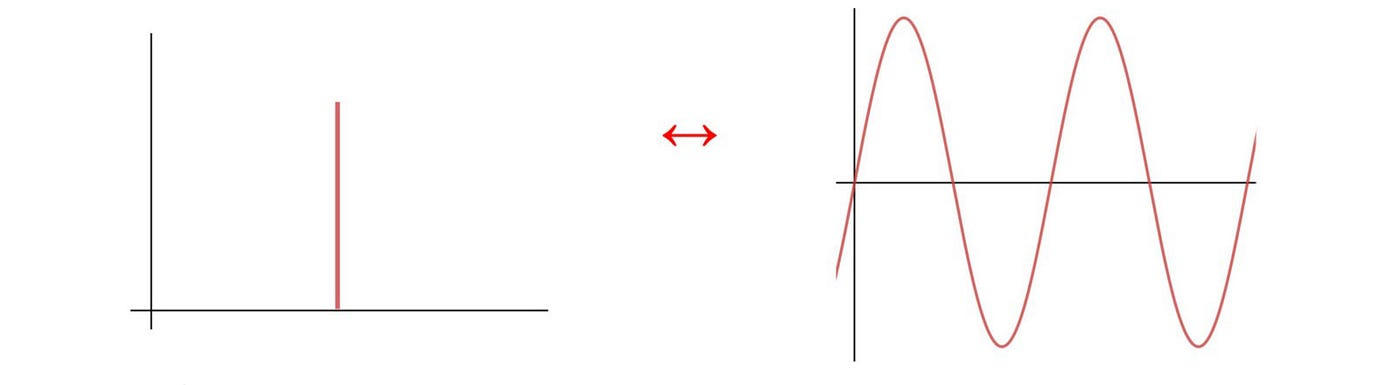

Instead, we need to use a Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT) to transform the periodic function from time space to frequency space. The technical details are a bit involved, but roughly speaking QFT behaves similarly to a normal Fourier Transform, so a periodic function like f(x) transforms into an impulse function, causing the state when measured to collapse with high probability onto a value from which we can determine r and by extension p and q.

That’s it! The details of how the Quantum Fourier Transform work are beyond the scope of my knowledge after a reading of Quantum Supremacy by Michio Kaku the Grifter, and the hardware problem of maintaining qubits that enjoy a state of superposition also seemed extremely involved; I have no intuition for how that works. Nevertheless, I found the general trick of taking advantage of periodicity of the mod function and then converting it to something like an impulse function in the frequency domain quite elegant and instructive on how we are able to recover anything useful from the parallel states in a quantum computer, even while the “parallel worlds” suggested by quantum physics seems to have no impact on our day to day life.